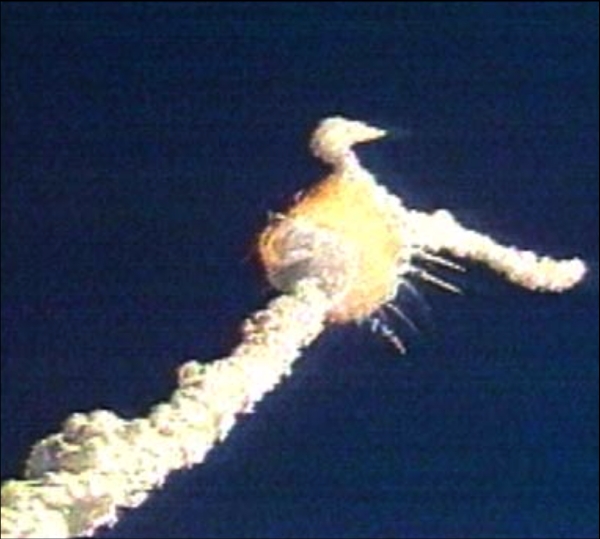

The story of the 1986 Challenger disaster is every bit as compelling as that of the Titanic. It was rushed into launch by a PR machine intended to boost the sagging popularity of the Space Shuttle, which had come to be seen by many as pointless and expensive. School teacher Christa McAuliffe was chosen from thousands of civilians to travel onboard, bringing space to the people, while simultaneously showing how safe it was to travel into orbit.

Unfortunately, that assumption of safety had led to a soon to be catastrophic drop in standards. Engineers from Morton Thiokol, the makers of the solid rocket boosters, pleaded with management not to launch below 40 degrees Fahrenheit, as they could not guarantee that the rubber O rings in the seals would function correctly below that temperature. However, having already delayed the launch several times, and with pressure growing from all sides, they were overruled and the risk of failure was deemed acceptable.

It was less than 32 degrees on the morning of launch, January 28th, 1986.

Richard Feynman was appointed to the investigation commission where his unstoppably curious mind and uniquely independent position meant he could cut through the political smoke.

Ultimately he uncovered a management team at NASA which had little grasp of the science needed to inform their decisions. He scorned at their complete lack of understanding of probability and therefore risk, deriding their estimate that the chance of spacecraft failure was 1/100,000, calculating it himself to be less than 1/100. At a televised public hearing into the disaster, Feynman famously put a piece of the rubber O ring into a glass of ice water for a few minutes and was able to show, simply to a non scientific audience, how the rubber lost most of its elasticity under freezing conditions, just like they had on the morning of the launch. He finished his demonstration with the memorable line “I believe that has some significance for our problem” Political forces were still at work however and Feynman threatened not to sign the final report after some of his contributions were omitted and observations downplayed.

He would not be silenced, and the commission eventually compromised for an appendix to the report in which his damning assessment of NASA management was published in full. He ended the appendix with a poetic line of wisdom. “For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled.”

Firstly, this great 4OD documentary tells the full tense, tragic and enthralling tale – Challenger: Countdown to Disaster.

Secondly, The Challenger is a dramatic retelling, by the BBC, of Feynman’s quest to solve one last major puzzle before he died. William Hurt brilliantly captures Feynman’s genius, integrity and unbending determination to get to the truth. The Challenger

Finally, a detailed examination of the explosion by NASA shortly after the disaster in 1986. Challenger Accident Investigation